In this post we'll look at how to approach problems reactively where we program according to what events can happen in our app.

Use reactive, RxJS-based solutions for complex problems

Summary

- There are certain scenarios that really lend themselves to a reactive solution - and they mainly involve the passage of time and the coordination of multiple asynchronous events.

- In this lesson, we'll look at some examples and introduce our first problem: how do we show a spinner on the screen when there are tasks happening in the background?

Transcript

Whenever I have to build a new feature, or I get a requirement specification, the decision of whether to use RxJS depends on two things for me.

Do I need to worry about timing?

An example can be as simple as, does it involve async operations? Or even as straightforward as, we need to wait three seconds before making an HTTP request.

The second question I ask myself is,

do we need to coordinate a lot of events that might be of different types like clicks or HTTP requests or even setTimeouts?

Again, an example can be wait for the user to click login then make a pull request. Then when that's done, we direct to the account page.

To even more complex examples like building a typeahead component where we need to coordinate the user hitting the keyboard with how much time has passed since the last keystroke with making a request to the server to search.

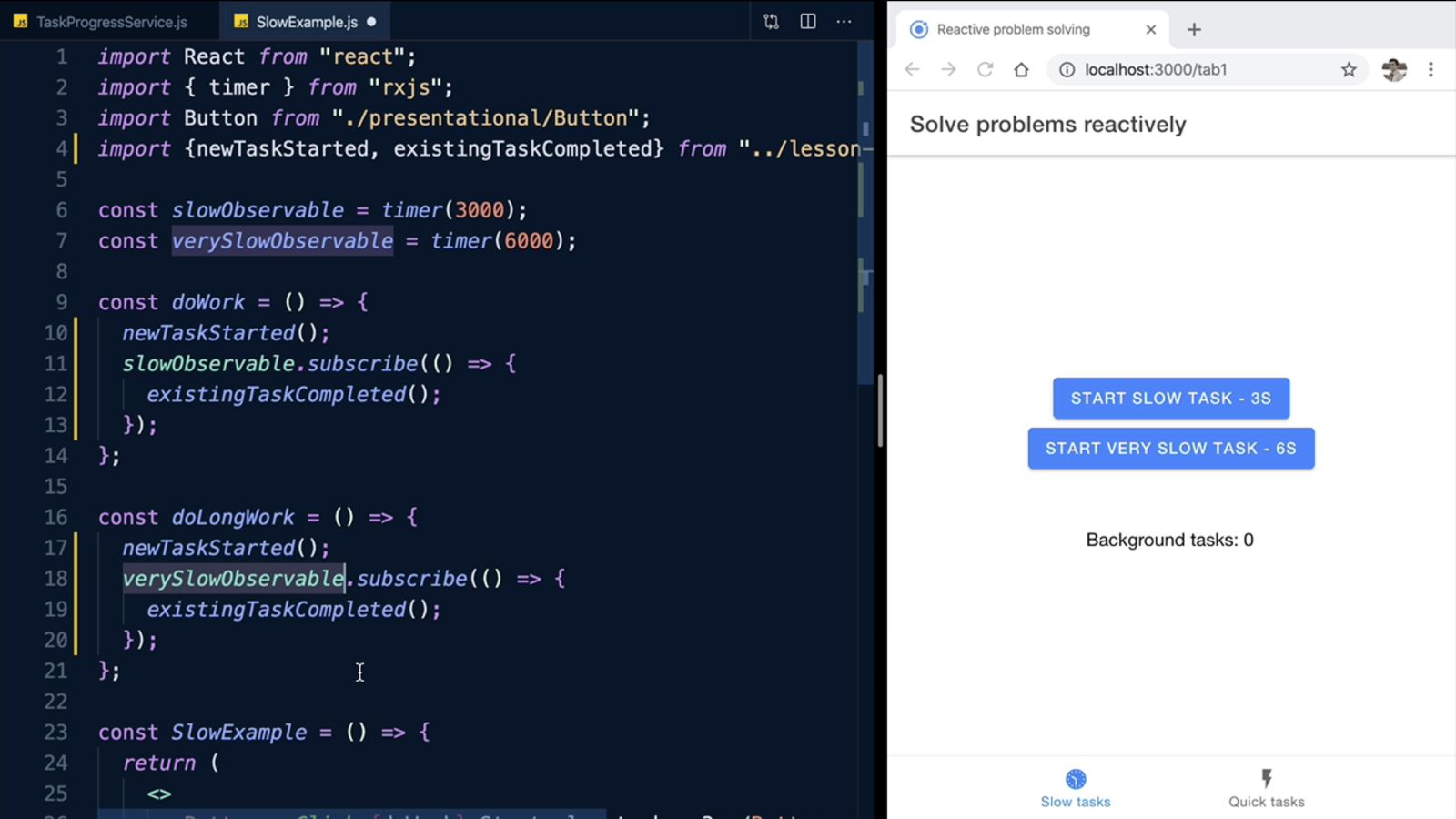

This is the app we'll be working with. When we click these buttons, we trigger some tasks in the background. Imagine slow HTTP request if you want.

App Overview

Our first requirement that we need to build straightaway is to show a loading spinner at the bottom of the app anytime there are any tasks happening in the background. We have a counter here that shows us how many of these tasks are happening at any point in time.

When we start some tasks, we notice it goes up and then it goes back down again as they start to finish. This indicator is only for explanation purposes here, so you get an idea of what is happening in the background, but we're going to solve the problem as if this doesn't exist at all.

This requirement is time-based. We don't know how long the loader is going to be on the screen, but it will be there for some time, that's for sure. It does involve coordinating different events. We need to coordinate all events happening in the background. I'd say it's a perfect fit for an RxJS reactive-based solution.

Problem Requirements

As with everything in software development, if you build something simple, the case for using RxJS isn't that big, but the decisions you make early will have a compound effect the more your app grows.

Time Diagram

The moment you introduce the concept of time in an app, however simple it may be initially, there's a chance that future requirements will build on that concept. You'll have ever more complex scenarios where you have to consider time, as we shall see.

Decision to use RxJS:

- Is there async or wait time? (timing is involved)

- Do we need to coordinate lots of even types? (clicks, keyboard events, http requests)

Requirements for app:

- Show a loading spinner when anything is happening in the background

- definitely time based!

- involves coordinating all events happening in background

- perfect for RxJS solution!

Break down a requirement into small problems

Summary

- We will introduce our first requirement: showing a loading spinner immediately when tasks are going on in the background. We will then break this requirement into more and more specific english sentences, which we will later turn into actual observable stream.

Transcript

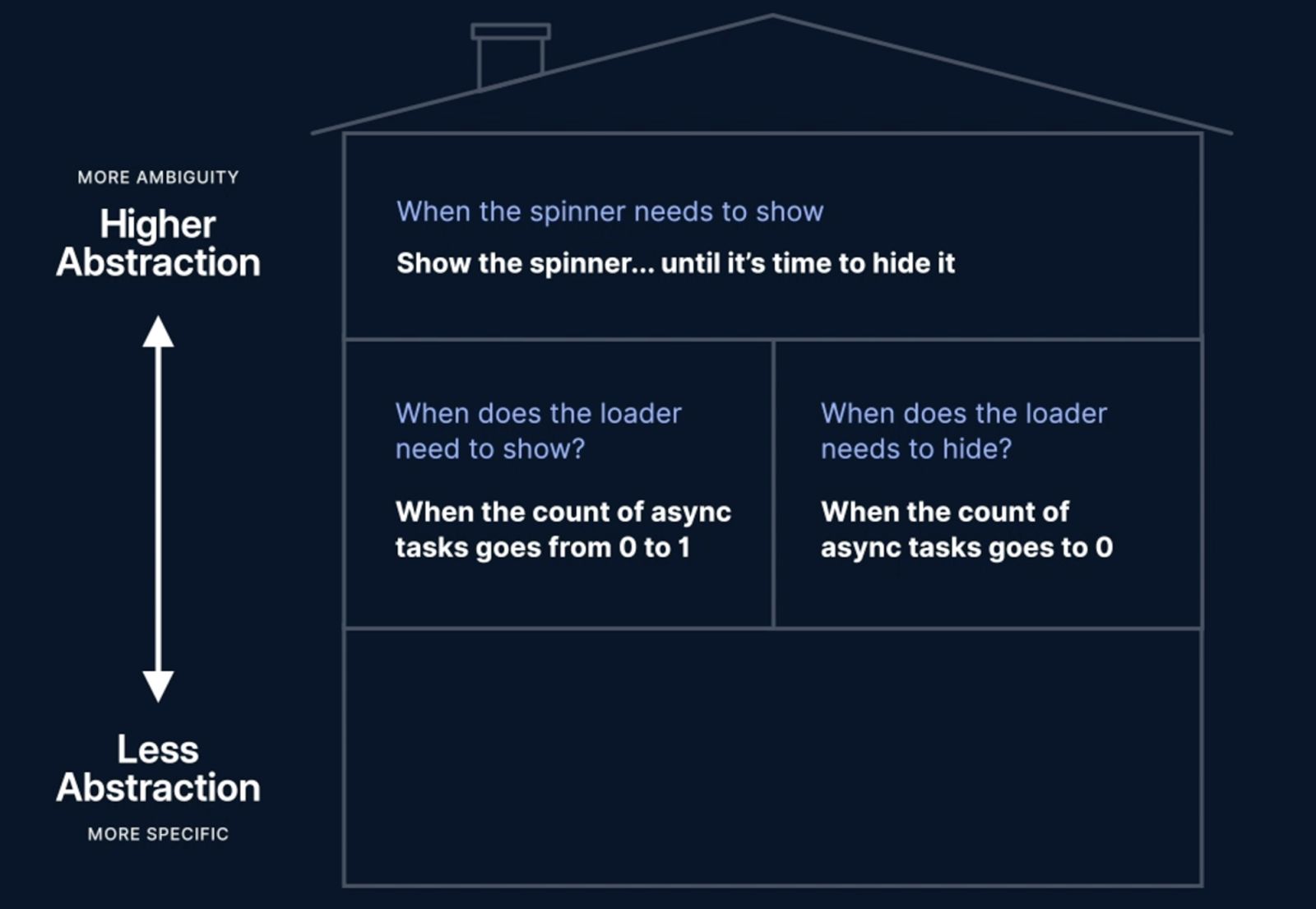

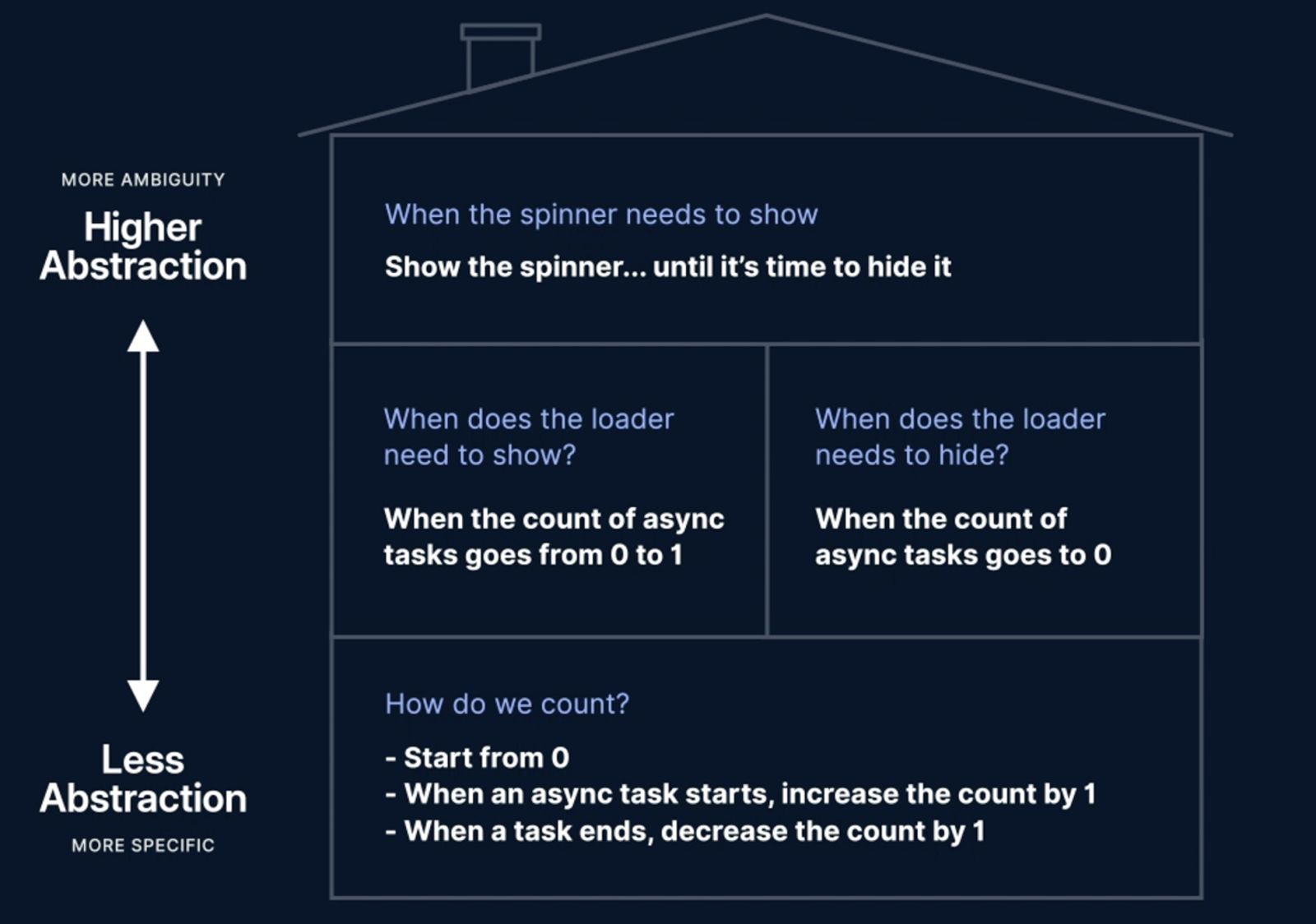

Our virtual manager comes in and tells us that we need to build a spinner for the app that will show any time there's any task going on. Instead of rushing to implement, let's try and break down the problem that we're trying to solve. I'll use this drawing of a building as an analogy for obstruction levels.

Obstruction Levels Drawing

The top floor is our highest level of obstruction and that's where we'll start. What's another way of thinking about the requirement? Well, when the spinner needs to show, show the spinner until it's time to hide it.

Obstruction Levels Drawing - Top Level

Because we're at the highest level of obstruction, this way of seeing the problem is the most ambiguous because we still have no idea what any of these three things mean. But it's also the closest interpretation to our requirement. If we solve this, we solved our problem.

Let's keep moving down and try to make this more specific by answering some of these questions. When does the loader need to show? Well, when the count of async tasks goes from zero to one. Let's explain this other part now. When does the loader need to hide? Well, it needs to hide when the count goes to zero.

Obstruction Levels Drawing - Middle Level

Notice how we stayed at the same level of abstraction with these two sentences. We still don't know how we would get the count of async tasks. How do we count? Well, we start from zero and when an async task starts, increase the count by one. When the task ends, decrease the count by one. We'll stop here.

Obstruction Levels Drawing - Bottom Level

Our goal was to start from something that resembles our initial requirement really closely, something vague that we wouldn't really know where to start solving. Break that down into more and more specific problems all the way to this, a simple counter that we can actually start tackling.

If we look closely, we broke down and explained almost everything. We still have some unknown sources like what is async task starts? What is task ending? Even, what is show the spinner?

If we had these free sources, then we could really nicely start going up to building and solve our problem. The nice part about solving problems this way is that we can imagine that we actually do have them. I'll just define taskStarts as a simple Observable() for now. I'll do the same for taskCompletions. The same for show spinner. I'll just go ahead and import the Observable token.

TaskProgressService.js

import { Observable } from 'rxjs';

const taskStarts = new Observable();

const taskCompletions = new Observable();

const showSpinner = new Observable();

export default {};

The great thing about breaking down our problems into small chunks like we did with the floors of our building is that we can define placeholders for any unknown sources and assume they already exist. This keeps us focused on solving our problem, one floor at a time.

Breaking Down the Problem:

- Show a spinner...until we hide it...

- When does the loader show? When the count of async tasks goes from 0 to 1

- When does the loader hide? When the count goes back to 0

- Define when an async task starts

- Define when an async task ends

- What does "show spinner" even mean!?

Start with simple definitions: taskStarts, taskCompletions, showSpinner as Observable()

remember to import { Observable } from 'rxjs'

Pipe events to numbers and maintain a running count using the scan operator

Summary

- In this lesson, we will use the simple data sources we created earlier, to create a more specialized stream that gives us the current count of tasks that are in progress.

Transcript

Let's look at the first problem we have to solve. I'll paste it here so we can follow more easily. I'll use my raw initial sources that I have up here to create a more specialized loadUp Observable that emits 1 anytime a task starts.

TaskProgressService.js

import { Observable } from 'rxjs';

import { mapTo } from 'rxjs/operators';

/*

How do we count?

Start from zero

When an async task starts, increase the count by 1

When a task ends, decrease the count by 1

*/

const taskStarts = new Observable();

const taskCompletions = new Observable();

const showSpinner = new Observable();

const loadUp = taskStarts.pipe(mapTo(1));

export default {};

I'll do the same thing for a loadDown Observable that emits a -1 anytime a task completes. Now, we can use these two to combine them into an even more useful loadVariations Observable that gives us +1's and -1's, depending on how tasks are starting and ending.

import { Observable, merge } from "rxjs";

...

const loadUp = taskStarts.pipe(mapTo(1));

const loadDown = taskCompletions.pipe(mapTo(-1));

const loadVariations = merge(loadUp, loadDown);

Notice how I've imported mapTo from the "rxjs/operators" package because it's meant to be piped and merged because we're actually using it to create a brand new Observable. It's being imported from the root "rxjs" package.

Let's celebrate progress. We're already in a much better position than when we started. This Observable is actually all we need from now on to solve our problem. We can forget anything that we have up here.

I'll actually make this more obvious and use the special comment from now on to mark that we can stop worrying about anything we have above it. This helps us work in a very restricted space. My cognitive demand is much lower when I can be sure that all the context I need to keep in my head is what I have highlighted versus this whole page.

const loadUp = taskStarts.pipe(mapTo(1));

const loadDown = taskCompletions.pipe(mapTo(-1));

// xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx //

const loadVariations = merge(loadUp, loadDown);

Because we're pretending that we don't have access to whatever is above this, variable names are very important when we work like this. We shouldn't really have to go back up to see how all of this works. It should make sense from its name.

We'll consider our current problem solved, if we have this, an Observable that gives us the currentLoadCount of tasks in our app. We'll start with our loadVariations Observable. Because we need to maintain a running count between emissions, I'm going to pipe() that to a scan(). I'll quickly go up and import it.

import { mapTo, scan } from "rxjs/operators";

...

const loadVariations = merge(loadUp, loadDown);

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

scan()

)

scan() has the same API as the reduce() array method. It accepts a function, which will receive two arguments, the totalCurrentLoads and the changeInLoads. Our variation that we get from here. What it's going to return is the previous load count (totalCurrentLoads) to which we will add the new change in the number of loads (changeInLoads).

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

})

);

It also accepts a starting value after our function and we wanted to start from zero.

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

}, 0)

);

Just to quickly go back and recap, the moment the task starts, it will get mapped to a number one so loadVariations will limit to one, which will in turn increase the count by one. If a task ends, it will get mapped to a -1, so loadVariations will emit the -1 which will decrease our count by one.

We started from some very raw streams, and we used those to create two more specialized streams. Then we combined those to create an even more useful stream, all the way up to this. A stream that whenever somebody subscribes to it, they'll get the current number of loads in our application.

First Problem:

How do we Count?

Create a loadUp and loadDown Observable to emit 1 and -1 when tasks start or complete, using mapTo:

import { mapTo } from 'rxjs/operators', because we will be usingpipeconst loadUp = taskStarts.pipe(mapTo(1))const loadDown = taskCompletions.pipe(mapTo(-1))

import merge from rxjs to create a new Observable

const loadVariations = merge(loadUp, loadDown)creates newObservablethat combines the two

**loadVariations is now all we need to solve our problem!**

Cognitive demand is much lower when we only need to deal with fewer pieces of information, and they are intelligently designed/named so that we can easily understand what they do (re: the naming convention of loadUp, loadDown and loadVariations.

We can consider our problem solved if: we have an observable that gives the currentLoadCount of tasks in our app. So lets make it!

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

}, 0)

scanshould be imported fromrxjs/operators, and accepts the same parameters asreducein JS, including the starting value after the function (which is0here)- We need to make

currentLoadCountwork as predictably as possible.

Good abstractions are predicatable

We won't get anything until

currentLoadCountemits something, so we need it to initially emit0To accomplish this:

- import

startWithfromrxjs/operators - add

startWithto ourcurrentLoadCountfunction like this:

- import

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

startWith(0);

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

})

We can now remove our starting value 0, and let our startsWith(0) flow through the scan function to return 0 initially

Create safe and predictable observable abstractions

Summary

- Because we're thinking in terms of very isolated layers of abstractions, we're also looking to build well abstracted observables that make sense on their own. One way you could figure out if an observable can live on its own is: If I threw my initial requirement away, could this observable still be useful for something else?

- As part of building well designed abstractions, we need to assume they can be used in any context, and not just in the one we're focused on building at the moment. So we need to make them as predictable as possible to consumers.

- In this lesson, we'll ensure that the stream we built previously guards against situations where we have more task completions than starts, and also always gives an initial value.

Transcript

Our currentLoadCount Observable is great and useful. Anybody can subscribe to it and they'll get how many tasks are currently loading in their application. Because we can't assume who will subscribe to it, how it will be used, we need to make it work in a very predictable fashion, so it doesn't bring surprises to consumers.

Good abstractions are as predictable as possible. If somebody subscribes to this, they won't get anything until this (loadVariations) emits a value. Which is not right. We know that the count is 0 initially so might as well emit 0 and then start tracking properly as tasks begin to start and finish. This scenario is captured in our requirements, start from zero and the nice thing about RxJS is that it usually flows like an English instruction. Let me just import the startWith operator. We want to startWith(0) because startWith now gives us the initial value, we don't really need the second argument to scan().

TaskProgressService.js

import { mapTo, scan, startWith } from "rxjs/operators";

...

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

startWith(0),

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

})

)

To put that differently, if you don't give an initial value to scan(), it will just let the first value it gets flow through it. Any consumers to this will get 0 immediately, and this function won't even get called for that initial value. Once we start getting more values after that, it will start getting called and it will start adding values to the initial one.

Another problem is what happens if for some reason we get way more taskCompletions than taskStarts? I don't know why that would happen, but this (currentLoadCount) would start going into the negative which, again, doesn't really make sense.

Let's extract this into a variable and say that if it's smaller than 0, return 0, otherwise, just return the new actual amount. Nice. This doesn't get into the negative. If we do get to the scenario where we get way more completions than starts, this will just keep emitting 0 over and over again which is not a huge problem.

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

startWith(0),

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

const newLoadCount = totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

return newLoadCount < 0 ? 0 : newLoadCount;

})

);

Again, as good abstraction builders, we want to be as predictable as possible to our consumers. I'll go up and import the distinctUntilChanged operator. I'll use it here to filter subsequent values which are equal.

import { mapTo, scan, startWith, distinctUntilChanged } from "rxjs/operators";

...

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

startWith(0),

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

}),

distinctUntilChanged()

)

What happens if we get more taskCompletions than taskStarts?

This shouldn't happen, but we can safeguard against this anyway by changing the function to check if newLoadCount is < 0 and return 0 if it is, to prevent going into the negative.

BUT then we might emit 0 over and over!

RxJS to the rescue!

- import

distinctUntilChangedfromrxjs/operators - place this at the very end of

currentLoadCount - this will filter subsequent values that are equal (like repeating

0s)

Maintain shared observable state using the scan and shareReplay operators

Summary

- The

scan()is very useful in RxJS. It allows you to maintain a running state over time. In this lesson, we'll look at some of the state types scan can hold: transient or single source of truth, and how we can achieve each of them by combining it with the share operators. - We'll also look at the differences between

share() / shareReplay(1) / shareReplay({bufferSize: 1, refCount: true})and how to avoid memory leaks when using them.

Transcript

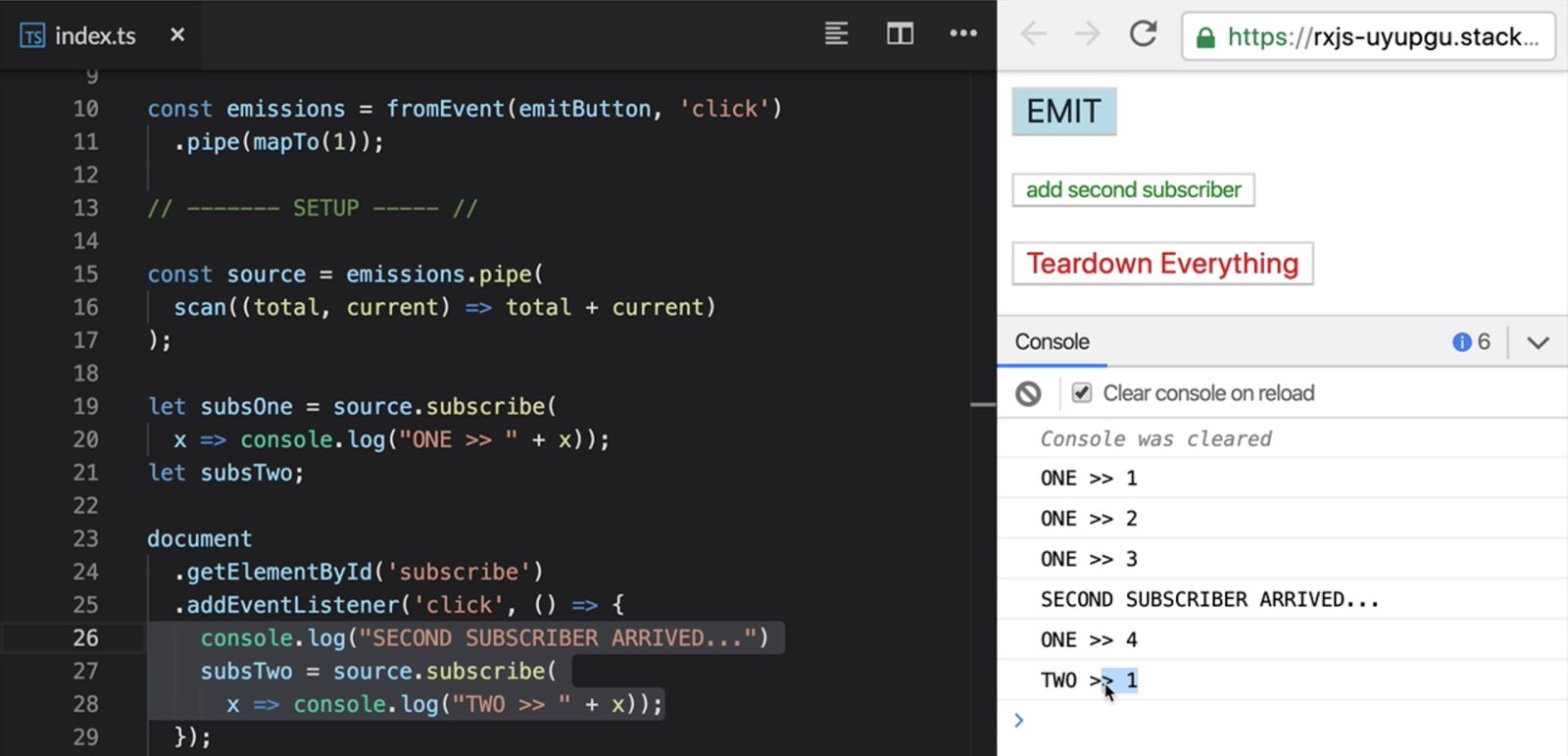

We'll take a quick break from building our app to look at this. An emissions Observable that emits a one anytime we click on this button (emitButton). If we look at the console here, when we click on EMIT, we get an emission. We pipe() these emissions to a scan() that adds up the numbers in the same way we've been doing in our app.

Emit Button

If we click multiple times, we get increasing values. We .subscribe() to this here, hence why we get the console logs. Have a look at this, if I click this button here (add second subscriber), it will add a new subscriber to our source. This is the callback where we actually subscribe.

Add Second Subscriber

If you click on EMIT now, we can see that our first subscriber got an expected state, the number four, but our second subscriber got a number one which is the initial state. scan() actually keeps a brand new state for each subscriber.

Unexpected Output

Another way you can think about this is what type of status can hold it? Is it transient? Do we want to reset it per subscription? We'll see an example of this later on in our app. Is it a single source of truth that is shareable across all subscribers? A Redux store would be a good example of this. It's shared and you definitely don't want it to reset per subscription.

Let's add the share() operator after our scan(). We emit only to the first subscriber initially. Once we bring in the second subscriber and then we emit, we get the same state for both of them now.

Shared Output

That's great, but after we added the second subscriber, there was this period of time where we didn't really know what the latest value is. The second subscriber only got that value once the source emitted again.

Let's switch this to a shareReplay() of (1) and then emit a bunch of times and then add the new subscriber and we can see that it gets a new value straightaway. For any future values, they'll be in sync again. This one is our buffer size. It means that it will hold the latest one value and send it immediately to any new subscribers. So our scan() state is now a single source of truth. It's shared and immediately knowable by all new subscribers.

Share Replay Example

If we click this button, Teardown Everything, it's going to unsubscribe from both of the subscriptions that we created. We can see that down here in the code as well. If we click on EMIT, we click multiple times, we just keep clicking and we don't get any messages now, which makes sense.

Let's try and add the second subscriber back end. What state do we get? We get 29. Where is this actually coming from? Well, it turns out that if you use the default mode of shareReplay(), it will keep a subscription to its source live even after everything has unsubscribed from it.

All that time we were clicking on emit thinking it had no effect, it was actually racking up values in the background silently. That's why we got all the way up to 29. This is also potentially dangerous for memory leaks as it will never unsubscribe from the source.

Instead of one, we'll pass in this object where we explicitly set the bufferSize to one and the refCount to true. refCount will keep track of our references, our subscribers and when the number of subscribers drops to zero, it will also dispose of its source.

If we try that again, we emit a bunch of times, we add a new subscriber, then we unsubscribe from everything and now we're going to emit a bunch of times in the background. Once we have the second subscriber, now we don't get any value because there's no initial value. We can see that now when we could click emit, we're going to get the value one again. Most of the time, this is the safe way to use shareReplay() and you want to use this option.

Share Replay Safe Option Output

Let's go back to our app and think about their scan(). This would definitely fall in the second category. As our currentLoadCount is a single source of truth, there's only one true count of background tasks at any one point in time.

Let's add shareReplay() at the end of it. I'll just import it up here.

TaskProgressService.js

import {

mapTo,

scan,

startWith,

distinctUntilChanged,

shareReplay

} from "rxjs/operators";

...

const currentLoadCount = loadVariations.pipe(

startWith(0),

scan((totalCurrentLoads, changeInLoads) => {

return totalCurrentLoads + changeInLoads;

}),

distinctUntilChanged(),

shareReplay({bufferSize: 1, refCount: true})

)

- Taking a look at an emitter similar to our app, we can see that

scanwill keep separate states for separate subscribers, allowing us to return a running total for each subscriber - Another way to consider this:

- what state is

scanholding?- transient?

- a single source of truth?

- Can add

share()to give each subscriber the same value, but we don't get the current value when we add a subscriber - If we instead use

shareReplay(1), we get the current value only for the added subscriber, and then we continue to increment thereafter, for each added subscriber - Problem: default of

shareReplaywill keep a subscription source "alive" in the background which will keep racking up values, even after everything has unsubscribed from it- to fix this we can alter

shareReplay:shareReplay({ bufferSize: 1, refCount: true })refCountwill keep a reference of our subscribers, and when the number of subs drops to zero, it drops its source.

- to fix this we can alter

- what state is

Back to Our App...

- Our

currentLoadCountis a single source of truth, so we do not want to keep a background task count. - Add

shareReplaythe same as above at the end of thecurrentLoadCountfunction

Use the filter and pairwise operators to determine when to show and hide the spinner

Summary

- Having access now to an observable that tells us when the in-progress task count changes, we will use it to create two even more specialized streams that will bring us close to solving our initial problem: an event stream that fires when we need to show the spinner and another that fires when we need to hide it.

- We will be using the pairwise and filter operators.

Transcript

We solved this problem and now we can move up one floor of obstruction. I'll copy this to our source page, and I'll copy this comment over here, just to mark that we're moving up one level of obstruction in our code as well. We're building an observable that's going to answer this question. Let's name it accordingly.

TaskProgressService.js

/*

When does the loader need to hide?

When the count of async tasks goes to 0

*/

const shouldHideSpinner =

export default {};

When the count of async tasks goes, we'll start with our currentLoadCount and once that goes to 0, we want to emit. I'll pipe() this to the filter() operator. We'll just go to the top and import it. It's only going to let values through that are 0.

TaskProgressService.js

import {

mapTo,

scan,

startWith,

distinctUntilChanged,

shareReplay,

filter

} from "rxjs/operators";

...

/*

When does the loader need to hide?

When the count of async tasks goes to 0

*/

const shouldHideSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

filter(count => count === 0)

)

We don't care that this (shouldHideSpinner) emits 0. We don't care what it emits. We just care when it emits because that's the time to hide the spinner.

Let's pick our second requirement. I'll just paste it here. Now we'll build an Observable that answers this question, . We'll name it shouldShowSpinner. Again, we need to listen to the count. We'll pipe() this to a filter() function again that will only let emissions go through when the load is 1.

/*

When does the loader need to show?

When the count of async tasks goes from 0 to 1

*/

const shouldHideSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(filter(count => count === 0));

const shouldShowSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(filter(count => count === 1));

This is not really right because we can go from a count of 2 to a count of 1 and then this (shouldShowSpinner) will emit, but that doesn't really mean that we have to show it. It's already showing. This part is really important.

We need to keep track of the previous value, as well as the current one and only emit when the previous is 0 and the current is 1. This is not going to work as it is. filter() only works with the current value. How do we keep track of the previous?

/*

When does the loader need to hide?

When the count of async tasks goes to 0

*/

const shouldHideSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

filter(count => count === 0)

);

const shouldShowSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

filter((prevCount, currCount) => prevCount === 0 && currCount === 1))

);

Well, scan() is one option. It allows us to keep track of previous state, but RxJS has a lot of operators that are named really well. If we can pretend for a moment that we just looked through the RxJS API, we notice that we can import the pairwise operator.

If I go back and add it, we'll see that it emits a tuple of the previous and the current value. We're just going to use some destructuring here to get the previous (prevCount) and the current count (currCount) from pairwise.

import {

mapTo,

scan,

startWith,

distinctUntilChanged,

shareReplay,

filter,

pairwise

} from "rxjs/operators";

...

/*

When does the loader need to hide?

When the count of async tasks goes to 0

*/

const shouldHideSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

filter(count => count === 0)

);

const shouldShowSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

pairwise(),

filter(([prevCount, currCount]) => prevCount === 0 && currCount === 1))

);

Even though we could have done this with scan(), with pairwise() we signal our intent much better to other developers reading this. The more operators we know, the bigger the chance that we're going to find a nicely named obstruction that signifies intent much better than a custom solution.

Now we can move up a layer in abstraction...

When does our loader need to hide/show?

- hide when the async count gets to

0 - show when the async count goes from

0to1

- hide when the async count gets to

Let's name our

Observableaccordingly:shouldHideSpinner- we import the

filteroperator and usepipeto pass it to the current load count, and check that the count is equal to0

const shouldHideSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

filter(count => count === 0);

);

Now we can check when to show **our spinner...

- again, we name accordingly:

shouldShowSpinner - again, we listen on the

currentLoadCount and again, we use

filterWe could filter and return any time the

countis equal to1, but that's not really right- what about when the count goes from 2 to 1? We don't need to show the spinner again. We just need to know when to show the spinner initially, when the count goes from 0 to 1.

- So, we need to keep track of the previous count... But how?

We can import the

pairwiseoperator, which emits the previous and current count.Here is our final

shouldShowSpinnerfunction:

const shouldShowSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

pairwise();

filter(([prevCount, currCount]) => prevCount === 0 && currCount === 1)

)

Build an observable from a simple english requirement

Summary

- Having built all the event streams we need, we can now assemble them and generate the observable equivalent of our main requirement sentence: “When the loader needs to show, show the loader, until it’s time to hide it”.

Transcript

We started from some very low-level terms like tasks starting or ending. We went up our floors tackling one small problem at a time creating higher and higher-level abstractions that eventually brought us to being able to solve our top-level requirement. We now have all the pieces we need for this. Let's go and assemble it.

Obstruction Levels Diagram

I'll add a comment for this new layer as well. When the spinner needs to show, show the spinner. Remember, we consider showSpinner to be an observable that when activated, shows the spinner. We're not going to worry yet about how that's going to work. When a task starts, switch to displaying the spinner until -- and I'll pipe() this to a take until -- until it's time to hide it.

TaskProgressService.js

// xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx //

/*

When the spinner needs to show

→ show the spinner..until it's time to hide it

*/

shouldShowSpinner.pipe(

switchMap(() => showSpinner.pipe(takeUntil(shouldHideSpinner)))

);

export default {};

We don't really care what or when this Observable emits. This is meant to be a top-level overview of how everything is wired up. We don't really need to reuse it, but we do want to activate it. I'll just .subscribe() to it in here.

shouldShowSpinner

.pipe(switchMap(() => showSpinner.pipe(takeUntil(shouldHideSpinner))))

.subscribe();

The moment somebody imports this file, this Observable will be activated. Yes, it will live on for the duration of our app. We never unsubscribe from it, but that's something we're OK with because we do want this to keep tracking tasks for the lifetime of our app.

To recap, we've marked our low-level building blocks and we kept assembling them into more powerful building blocks, but we also made sure not to dump everything in the same stream. Instead, obstruct the obstructions that make sense on their own.

Not only does this keep our RxJS code more readable, almost flowing like an English sentence, but it also allows us to reuse some of these should we need to do so later. And we will need to.

Highest Level of Abstraction Achieved! 🎉

- Now we can simply tackle our top level abstraction: showing the spinner until it's time to hide it...

- Currently, we consider

showSpinneranObservablethat when "activated" shows the spinner. - But we're not worrying about how it does that just yet.

When a task starts, switch to displaying the spinner, until it's time to hide it...

shouldShowSpinner.pipe( switchMap(() => showSpinner.pipe(takeUntil(shouldHideSpinner))) ).subscribe();

Expose complex reactive code as simple function based APIs

Summary

- Before we can test what we built, we need to go back to the empty Subjects that we used as placeholders to define when tasks start and end and actually connect them to our app.

- In addition, we will learn how to keep our external APIs simple, and avoid making our users understand RxJS.

Transcript

Now that we solved our problem, we can go back and focus on our Observables. How do we make them emit whenever a task starts or complete? Tasks come in all shapes and sizes. It might be an Observable that someone's just Subscribed to and we're waiting for it to emit or it might be a setTimeout() or even a fetch() request that's been fired off to some server.

/*

timer(6000).subscribe(...)

setTimeout(() => ..., 6000)

fetch('someapi.com', () => ...)

*/

We need to expose the most widely applicable API possible, so that whenever a task is created or completes, we can easily tell our servers about it. The most generic API you can think of is a function, a simple function that's called newTaskStarted, which is going to be exported from our service.

TaskProgressService.js

/*

timer(6000).subscribe(...)

setTimeout(() => ..., 6000)

fetch('someapi.com', () => ...)

*/

export function newTaskStarted() {}

const taskStarts = new Observable();

All somebody needs to do to tell us that a task has started is to import and call this. Let's do one for tasks ending as well. How do we tell this Observable to emit whenever this function is called? We can just use subjects Subject() and they've already been imported from the top-level package.

import { Observable, merge, Subject } from "rxjs";

...

/*

timer(6000).subscribe(...)

setTimeout(() => ..., 6000)

fetch('someapi.com', () => ...)

*/

export function newTaskStarted() {

}

export function existingTaskCompleted() {

}

A Subject() is both an Observable() and an observer. In other words, whenever we call .next() on this, it will also cause the Observable() to emit a notification to whoever is Subscribed to it. I'll just do the same for taskCompletions as well. Let's look at our project now.

/*

timer(6000).subscribe(...)

setTimeout(() => ..., 6000)

fetch('someapi.com', () => ...)

*/

export function newTaskStarted() {

taskStarts.next();

}

export function existingTaskCompleted() {

taskCompletions.next();

}

I have here some components. I'll just open up the SlowExample.js and also open the app to the side. These two buttons here are responsible for the two buttons on the first step. Whenever you click on the button, it Subscribes to an Observable that emits after three seconds or six seconds for the longer one.

SlowExample.js Overview

We have our service already imported here. I'm just going to pick our two exported functions. We want to call this whenever one of the buttons is pressed. We want to call existingTaskCompleted() right in the .subscribe() for both of the Observables. Basically, we consider them completed whenever they emit.

On Button Click Example

Why are we going from an Observable to a Function, back to an Observable again? Let's open up our code for the other tab. This is the component responsible for our second tab at the bottom. Here we're dealing with Promises. Because we've kept our API simple, we can now import our two functions (existingTaskCompleted, newTaskStarted) again and call newTaskStarted() before the Promises are created and newTaskCompleted() right before they resolve.

Now, whenever a button is clicked, it's going to tell our service that the new task has started. Whenever this Promise resolves after a few seconds, it's going to tell our service that a task has just completed.

Button Reactions

To recap, we've been taking advantage of RxJS to create readable streams of nicely flowing logic. We paid attention to how we create these obstructions to keep our solution maintainable and robust, but most code bases are not using RxJS.

To keep our features usable in as many places as possible, we exposed two simple functions to the outside world, and we connected those function calls to the sources that trigger all of our internal reactive logic via subject.

Now we can focus on making taskStarts and taskCompletions emit.

Tasks could be:

- an

observable - a set timeout

- a fetch request

- etc

To be widely applicable, we'll go generic and use a function called newTaskStarted

- (and

existingTaskCompletedfor when a task is completed) - Change each

observableto aSubject Then, inside these functions, call the associated subject with

next()- ie:

export function newTaskStarted() { taskStarts.next() }

- ie:

Then we import these functions into our React app's "slow" component, and call the

newTaskStartedfunction when the associated buttons are clicked.- We then call

existingTaskCompletedinside of thesubscribefor eachobservable. We consider them completed whenever they emit

Inside of our other "quick" component we are using promises. So in this case:

call the

newTaskStartedfunction right before the promise- and call

existingTaskCompletedwhen the promise resolves

RECAP:

- took advantage of RxJS to create readable streams of logic

- paid attention to how we maintain these abstractions

- to keep features usable, we exposed two simple functions that trigger all of our internal reactive logic via subject

- then imported these functions into a React app

Extend your reactive logic using observable-like proxies that delay or drop events

Summary

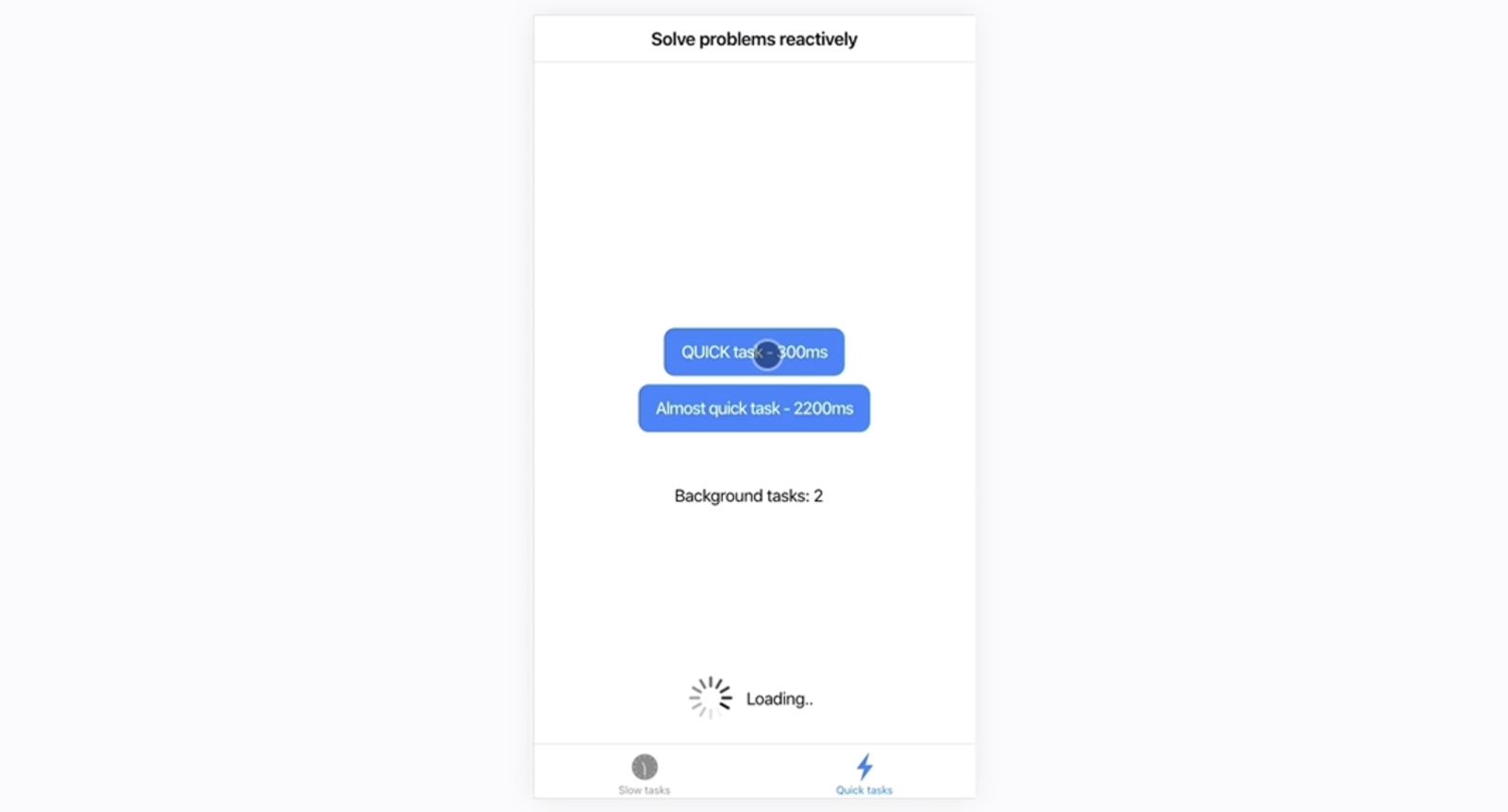

- Our app is working! But now our manager comes in and tells us that some tasks in our app are finishing very fast, so users are seeing a short glimpse of the spooner which makes the app look glitchy.

- Our new requirement is to wait at least 2 seconds before showing the spinner. So without introducing any complexity into our main observable, we will create a new intermediary stream that will be a proxy between the observable that immediately tells us when to show the spinner and the one that actual shows it. This new proxy will delay the events accordingly.

Transcript

This button here triggers a really quick task that's over in 300 milliseconds. If I click, the spinner appeared and quickly vanished. I'll do that again. Click, it appears and then vanishes. Not the best experience and it looks a bit glitchy.

Problem Overview

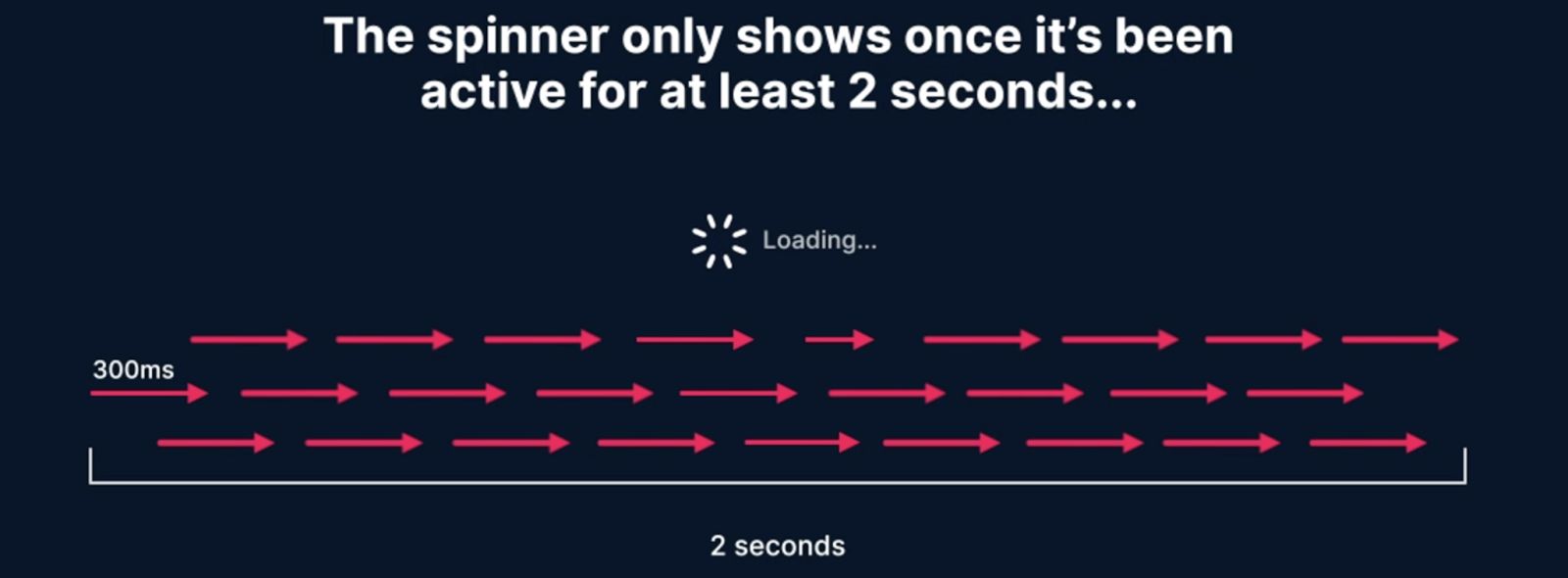

Our virtual manager tells us that I need to change the spinner, so that instead of showing it immediately, the spinner only shows once it's been active for at least two seconds. What does this mean?

Well, if you imagine a timeline of two seconds and you have a really quick task that only takes 300 milliseconds, then we don't want to show it. If we have a collection of very short tasks that continuously intersect each other over a period of two seconds, then we do want to show it in that case.

Quick Example

Continuous Example

If it's a case where we have even a small breakage between them, we don't want to show it because we consider these two separate independent instances that were less than two seconds each. Truth is, we don't even have to think about those scenarios.

Breakage Example

We've broken down our problems into very small bits. If we need to work at this level or this level or even this level, we don't even have to think about concepts down here, such as tasks starting or ending. I'll create a new floor.

The moment the spinner becomes active to waiting for two seconds before showing it, but cancel if it becomes inactive again in the meantime. The only inputs to this, the only information that we need to solve the problem are these two. When does the loader become active and when does the loader become inactive?

Obstruction Levels - New Floor

What's going to happen is now, this will be the answer we need for this question, when does the spinner need to show? Let's go to our code. I'll move right below the layer where we declared these two and I'll add a new comment. I'll copy our breakdown of the requirement.

TaskProgressService.js

const shouldShowSpinner = currentLoadCount.pipe(

pairwise(),

filter(([prevCount, currCount]) => prevCount === 0 && currCount === 1))

);

// xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx //

/*

The moment the spinner becomes active...

Switch to waiting for 2s before showing it

But cancel if it becomes inactive again in the meantime

*/

// xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx //

shouldShowSpinner

.pipe(switchMap(() => showSpinner.pipe(takeUntil(shouldHideSpinner))))

.subscribe();

First, let's rename these to be more indicative of what they actually do, spinnerDeactivated and spinnerActivated. For the new implementation of this, the moment the spinner becomes active, switch to waiting for two seconds before emitting.

// xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx //

const spinnerDeactivated = currentLoadCount.pipe(

filter(count => count === 0)

);

const spinnerActivated = currentLoadCount.pipe(

pairwise(),

filter(([prevCount, currCount]) => prevCount === 0 && currCount === 1))

);

// xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx //

/*

The moment the spinner becomes active...

Switch to waiting for 2s before showing it

But cancel if it becomes inactive again in the meantime

*/

const shouldShowSpinner = spinnerActivated.pipe(

switchMap(() => timer(2000))

)

We don't want to let the timer fire after its two seconds are up if the spinner became inactive in the meantime. I'll takeUntil() the spinner is deactivated. Finally, I'll need to make sure that I'm using spinnerDeactivated in here as well. Let's test this.

const shouldShowSpinner = spinnerActivated.pipe(

switchMap(() => timer(2000).pipe(takeUntil(spinnerDeactivated)))

);

I'll press it once, no spinner, even after two seconds. I'll press this a few times and the spinner now shows and keeps showing because there have been enough of these overlapping tasks over a period of two seconds to warrant showing it.

Overlapping Tasks

If I go back to the first tap and trigger a really slow task, we can see that it still works. In summary, breaking down our problems previously helped us easily find a spot for our new requirement.

Really Slow Task

It had two clear inputs that were already answered by these questions and it had a very clear output to our top-level requirement. All of that translated perfectly into our code as well.

Because we created well-encapsulated building blocks, we could simply declare another well-defined building block and insert it kind of like a proxy between these sources (spinnerDeactivated/spinnerActivated) and our top-level consumer (shouldShowSpinner). Our proxy simply responds to events from this (spinnerActivated), delaying them as necessary and fires them to the next block on the chain.

What if our async call is too quick to show the spinner?

- If an async call resolves too quickly the action of showing the spinner will appear as a glitch

- We should only show the spinner once it's been active for at least 2 seconds... but how?

New Abstraction: When the spinner becomes active, wait for 2 seconds before showing it. BUT cancel showing it, if it becomes inactive again in the meantime.

When does the spinner need to show?

- Rename

shouldHideSpinnertospinnerDeactivatedand renameshouldShowSpinnertospinnerActivatedto be more indicative of what they actually do (replace any usage of these functions in the rest of your code!) New

shouldShowSpinnerfunction:const shouldShowSpinner = spinnerActivated.pipe( switchMap(() => timer(2000).pipe(takeUntil(spinnerDeactivated))) )

Now the spinner will wait for 2 seconds before showing, and will not show when the action is too quick to warrant it

Love your beautiful face ❤️